Racial Injustice in America: A Framework for Georgetown’s Future Engagement

Lohrfink Auditorium

Georgetown University

My talk today addresses racial injustice, which persists in our country, is structural in its influence, and seems to be intensifying. I would like to reflect on this perpetual disgrace in the context of our university, where particularly over the course of the past 40 years, we have aimed to tackle injustice in various ways. As for racial injustice, we can claim that members of this very audience have pioneered in our efforts—in many cases at personal cost, as the progress of racial inequality, whether here at Georgetown, and certainly in the broader society, has moved at a painstakingly slow pace and involved multiple contractions. I hope in this talk to encourage all of us to pick up the pace: to commit to a more energized effort to address what has been the besetting conflict—evil—of our American society: racial injustice.

We, at Georgetown, have much to acknowledge, to celebrate, over these past 40 years, acknowledging the excruciating slow pace and compromises involved. I’m taking the period from the mid-1970s to today as my context because these years represent a period of intentional focus for Georgetown…and many of those responsible for this progress are here today. Let us celebrate the people whom we see, around us, who have helped us in understanding how difficult this effort of both integrating and promoting inclusion has been.

In 1976, Father Timothy Healy came to Georgetown, and it was during his years of leadership that Georgetown began a new arc of engagement.

Sam Harvey joined our community in 1976 and served as Director of our Center for Minority Student Affairs until he was named Georgetown’s first African-American Vice-President in 1988.

Gwen Mikell also joined our community in 1976 and later became the first African American to be tenured on the Main Campus.

Rosemary Kilkenny joined our community in 1980 as a Special Assistant to the President for Affirmative Action Programs, and now serves as our first Vice President for Diversity. Every year, Rosemary produces our University’s Affirmative Action Plan for the Department of Labor.

John Thompson Jr. arrived in 1972. His singular style of leadership for twenty-seven seasons as Head Men’s Basketball Coach is recognized by our community in our annual celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. day with the John Thompson Jr. Legacy of a Dream Award.

Our GEMS program at our Medical School was established in 1976.

Our Community Scholars Program is now more than four decades old.

We rededicated our Black House—founded in 1973—in a new and larger residence in 2013.

Over the years so many—Renee DeVigne, David Wilmot, Dennis Williams, Michael Smith, Monica Rascoe and Bill Reid and Joe Neale, Paul Cardaci, and Jim Slevin, and later, Tom Bulloch and Charlene Brown-McKenzie…there’s so many others, all who have made extraordinary contributions to our efforts.

None of this would have been possible without the work of these special women and men who have enabled Georgetown to unlock a potential that lay unfulfilled through much of our history.

At the same time, as these preliminary efforts were underway, Georgetown undertook an expansion turn, in our journey towards greater excellence. In the mid-1970s, Georgetown intentionally began moving from being a regional, undergraduate-centric institution to a national, research university. In recent years we have experienced stellar growth and development.

In the first years of this century:

- We have raised more money than in all of the years prior since 1789.

- Our endowment is now more than $1.5 billion.

- We have added $1.3 billion to our campus infrastructure, enhancing the homes for our Business School, the natural sciences, and the performing arts.

- We added our first new school in 60 years.

And while we have fully navigated the transition from regional to national—we have embraced the challenge of what it means to be a truly “global” university.

We have done this while seeking to intensify our commitment to the deepest values that have animated our community since our founding, including a commitment to justice, to supporting a range of disciplines and areas of research, and our openness to a world of ideas.

It is this understanding that we can never be static—that our journey of engaging primary issues of justice that characterizes the modern history of Georgetown—demands ever more of us continually.

What are the issues of injustice that are salient for us now—that demand further engagement for Georgetown, because they are so significant for our nation, for all of us?

This Moment—Addressing Structures

Not for the first time, hardly, but in the past year and half or so, we have been witness to “incidents” that shake our confidence in, for many, an assumption that as a country we were overcoming the legacies—and their structural groundings—of slavery, subsequent segregation, and systemic racism in so much of our lives.

Certainly, the transparency that characterizes the technologies we use, the ubiquity of access to images through new forms of media, our connection to one another, have enabled a flow of ideas and perspectives at a speed without precedent in history. At the same time, the underlying structures of what leads to these depictions are, and have been, there—for all to see; we just have better lenses today and are forced to see these structures squarely…to acknowledge their existence.

As such, highly visible incidents from Sanford to Ferguson, to Staten Island, to Cleveland, to Baltimore, to Charleston, to Chicago, to Flint…and so many more…these have shattered any hope that now in this…the eighth-year of our first African-American president, twice-elected, we were somehow moving into a post-racial society. Along with our cameras, we have the realization that we are hardly “post-racial.”

One hundred and fifty years after the abolition of slavery, American society is still grappling with the problems of racism and racial injustice regarding our citizens of African descent.

Recent public manifestations of racism and racial injustice have underscored the urgency of the need to address these problems—persistent income, housing, education and health disparities as well as public demonstrations against police killings, escalating crime rates, increasing unemployment rates, mass incarceration of blacks through unjust sentencing practices, environmental discrimination.

We are witnesses today of the ramifications of the American experience of racism traceable to the very settling of our country. What we witness must lead us to confront how continual racial injustice within the American context is manifest and how to identify creative responses to it. An authentic response from Georgetown recognizes our connection to this history—our effort to contribute as one of the world’s leading universities, our Catholic and Jesuit heritage and the resources of ecumenical and interfaith understanding.

That some of these incidents occurred during the years in which we celebrated the 50th anniversaries of Dr. King’s Nobel Prize, the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, that in 2016, before the Supreme Court we have another case challenging affirmative action in higher education, only adds to the sense of how much work is still required to realize that “abiding faith in America…an audacious faith in the future of mankind”1 that Dr. King spoke of upon receiving his Nobel Prize.

To be sure, the Academy—our nation’s colleges and universities—has addressed, to one degree or another, the persistent and enduring legacy of our past racial injustice, its history, and the structures that continue to underpin it. In a beautiful post, “On Whose Shoulders the Research Stands”, following his Atlantic Monthly cover story, “The Case for Reparations,” Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote:

“…this piece would not exist without the work of economists like Professor Darity, of historians like Barbara Fields and Tony Judt, of sociologists like William Massey and Devah Pager, of law professors like Kim Forde-Mazrui and Eric J Miller. And so on. Without them… all my writing, is significantly poorer. Without the academy, we are not talking right now.”2

We are in possession of insights that should mobilize us to address this legacy. These insights not only point to but illuminate a set of deep, structural issues that must be confronted if we are to realize the full promise of the American project.

These insights in Mr. Coates essay come from exceptional scholarship throughout the Academy, as he recounts:

Patrick Sharkey, a sociologist at New York University, studied children born from 1955 through 1970 and found that 4 percent of whites and 62 percent of blacks across America had been raised in poor neighborhoods. A generation later, the same study showed, virtually nothing had changed.3

…the Harvard sociologist Robert J. Sampson examined incarceration rates in Chicago in his 2012 book, Great American City…found that a black neighborhood with one of the highest incarceration rates (West Garfield Park) had a rate more than 40 times as high as the white neighborhood with the highest rate (Clearing).4

In 1860, slaves as an asset were worth more than all of America’s manufacturing, all of the railroads, all of the productive capacity of the United States put together,” the Yale historian David W. Blight has noted. “Slaves were the single largest, by far, financial asset of property in the entire American economy.5

We can find other markers of structural impediments in the dreary statistics of inequality: “Only 14% of African American eight graders score at or above the proficient levels.”6 Just over half of African Americans graduate from high school, “compared to more than three-quarters of white and Asian students.”7 At the root of these inequities are structural disadvantages—in school funding and in educational opportunity.

We spend more than $80 billion on incarceration–but whom do we incarcerate:

“The United States now accounts for less than 5 percent of the world’s inhabitants—and about 25 percent of its incarcerated inhabitants. In 2000, one in 10 black males between the ages of 20 and 40 was incarcerated—10 times the rate of their white peers.”8

People of color are significantly overrepresented in the US prison population, making up more than 60 percent of the people behind bars. Despite being only 13 percent of the overall US population, 40 percent of those incarcerated are black.”9

African-Americans were enslaved for 250 years before emancipation—post-emancipation did not bring equality; it brought Jim Crow. While there have been important achievements over the past one hundred and fifty years, we can’t deny the continuing and persistent effects of the original fault-line of this republic.

For a place like Georgetown, it is of special importance for us to recognize this history…to recognize its implications for our nation…and our responsibilities to one another.

Our heritage as a Catholic and Jesuit university calls us to respond to the demands of social justice. As a Catholic university, we draw from the deep tradition of Catholic Social Thought. In modern times this tradition has been captured in a series of fourteen encyclicals beginning in 1891 with Rerum Novarum of Leo XIII and continues to our present day with Laudato Si of Pope Francis. The development of this heritage has identified seven themes, and perhaps the most important is “solidarity.” To quote the U.S. Catholic Conference of Bishops:

“We are one human family whatever our national, racial, ethnic, economic, and ideological differences.”10

Pope Francis, speaking in Brazil in July 2013, said:

“…never tire of working for a more just world, marked by greater solidarity! No one can remain insensitive to the inequalities that persist in the world! Everybody, according to his or her particular opportunities and responsibilities, should be able to make a personal contribution to putting an end to so many social injustices.”11

As a Jesuit university we have also embraced a challenge that was presented by the Superior General of the Society of Jesus, Father Pedro Arrupe throughout his tenure of leadership from 1966 through 1983. Father Arrupe was acutely aware of the grave injustices in our world.

Having been expelled by the Republican government in Spain, having lived in Hiroshima in 1945, painfully aware of the oppressive regimes in Latin America—and the failure of some in the Church to come to terms with those injustices. In 1973, Fr. Arrupe laid the groundwork for a deeper challenge. In a speech entitled “Men and Women for Others,” he called on educators to undertake rigorous self-evaluation and “above all make sure that in the future the education imparted in Jesuit schools will be equal to the demands of justice in the world.”12

We, at Georgetown, have been responding to Father Arrupe’s challenge for more than four decades. We have not, however, sufficiently grappled with the problem of racial injustice.

This is not just a Catholic and Jesuit issue—it is a crucial moral issue that is both ecumenical and interfaith…that is strengthened by the cooperative engagement of the faith traditions which contribute so powerfully to the Georgetown experience. We can draw on this distinctive strength of Georgetown as we embrace this moment of opportunity for our community.

Moral Imagination and the “test of justice”

So, what can we do, at Georgetown, to contribute to the work of realizing Dr. King’s “abiding faith in America…an audacious faith in the future of mankind.”13 Our intentions, and our actions, must be animated by moral imagination.

David Bromwich, in a beautiful essay on Moral Imagination finds our understanding of moral imagination as beginning in Edmund Burke and his effort to understand the responsibilities of the British nation at a time of empire. The fundamental question of our moral imagination is to understand our responsibilities to those who we regard as “Other”—as different from ourselves. For Burke, “the test of justice of a moral imagination turns out to be justice to a stranger.” The question we must engage, in our time, is what is “the test of a justice of a moral imagination”, today, when we realize that “the stranger” is in fact our neighbor?14

There is no more urgent question facing our world than the question of understanding this “test of justice”: what are our responsibilities to one another, especially those who may be “other” than ourselves in this moment of unprecedented diversity and connectedness. And especially when we must realize that the “other,” again, is our neighbor, our fellow citizen, an individual.

Amin Maalouf shares with us the insight that the combination of elements which gives each of us our authenticity: “gives every individual richness and value and makes each human being unique and irreplaceable.”15

There have been moments in history when creative individuals…creative communities have responded to the demands of their times and found new ways to engage the world. John Hope Franklin—shaping a new history, Martin Luther King Jr.—fusing a philosophy of non-violence to the unfinished American project, Rosa Parks—deciding to take a different seat. In each case they understood the demands of their moment.

This is another such moment—for all of us, for Georgetown.

When John Hope Franklin, in 1958, provided a new framing of the history of our nation, he was exercising his moral imagination. Drew Faust captured the breadth of Professor Franklin’s moral imagination and the example he set for all of us in the Academy in a recent reflection on the centenary of his birth. President Faust writes:

But he knew that erasing the color line required far more than electing a black president. Until we had a new history, we could not build a different and better future. The fundamental requirement, what we—and now quoting Professor Franklin: ‘need to do as a nation and as individual members of society is to confront our past and see it for what it is. It is a past filled with some of the ugliest possible examples of racial brutality and degradation in human history. We need to recognize it for what it was and is and not explain it away, excuse it, or justify it. Having done that, we should then make a good-faith effort to turn our history around.’16

President Faust then concludes: “In other words, it is history that has the capacity to save us.”17 And I think to history, we can add—literature, philosophy, theology, sociology, psychology, anthropology, economics, business, political science, public policy, law, the health sciences: we need to focus our imaginations within each of our disciplines and across our disciplines and direct them to our faith in the future of humankind, one predicated on equality and justice.

We have seen the imaginations of scholars across the Academy like Greg Grandin, and Edward Baptist, Walter Johnson and Sven Beckert, Isabel Wilkerson and Bryan Stevenson, poets and performers—Claudine Rankin, Natasha Tretheway, Anna Deveare Smith, public intellectuals—Ta-Nehisi Coates, Melissa Harris-Perry—our own Adam Rothman, and Maurice Jackson, Michael Eric Dyson and Scott Taylor, Paul Butler, Marcia Chatelain, Gwen Mikell, Angie Mitchell and Robert Patterson, Soyica Colbert and Terrence Johnson and David Thomas, Pat King, Lucille Adams-Campbell, Sheryll Cashin, and Peter Edelman, Don McHenry—all bring an imaginative force resonant with the spirit Drew Faust associates with Professor Franklin.

Just over a month ago, following the recommendation of our Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation, we had a special ceremony in which we removed the names from two of our buildings, renaming them Remembrance Hall and Freedom Hall. At that time I shared these words:

Over one hundred and seventy years ago, people just like us lacked the moral imagination in their moment to recognize the responsibilities that we have to one another…to see the humanity and inherent dignity of all peoples.

Their days are not unlike our days.

Their moral failings are not unlike our own.

What would a fully alive moral imagination enable us to see in the challenges and injustices that we are called to confront in this moment?

This is the moment for us to find within each of ourselves and within our community, the resources of our moral imaginations to determine how we can contribute to responding to this urgent moment in our nation.

This is not a moment for us to say: “We are an old and venerable institution. We have been at this for many years. What more can we contribute?”

This is the moment for us to say: “Georgetown, today, is in a different place—because Georgetown is “in the world,” which changes and challenges us—and Georgetown has always aimed to be engaged in the world. It is in this place because of all of you, on the shoulders on whom we stand today. We now expect even more of ourselves, more of this institution. We have a new contribution to make at an urgent inflection point for our country.”

A Way Forward

This moment demands our engagement, in fact.

We live our lives here with a heritage on which we can build, a heritage we owe to others, many of whom are here today. We would not be the place we are today if it had not been for their efforts—Sam and Gwen and Rosemary, Coach, Renee and Don and so many of you who are here right now. We honor their efforts by how we respond to the moral urgency of this moment.

I have benefited greatly from my conversations with so many of you over so many years, and in recent weeks with those who have played such an important role in building our program in African American Studies—and especially, Robert Patterson, Angie Mitchell, Maurice Jackson, Doug Reed, Maya Roth, Joe Murphy, and Alise Carse. These colleagues have consistently—throughout their years here— called us to find the very best in ourselves and have served so selflessly over so many years.

We have all been the beneficiaries of the efforts of our Working Group on Slavery, Memory and Reconciliation, and the students who have raised their voices—to honor those whose role on our campus has been overlooked and unacknowledged: the forced labor of enslaved persons. Led by Father David Collins, this group of some of our University’s most distinguished faculty and committed students, staff and alumni is helping us to know this history, to memorialize it, and to inspire us to a better understanding of our present.

Our students have made extraordinary contributions to this work. Some who are here today have been part of a set of recent efforts to foster a community that is ever more diverse and inclusive.

Two years ago, a group of students organized through the Black House shared with me a set of recommendations to help improve the experiences of our students of color on campus. With their hard work and their leadership—and their close collaboration with our faculty—we now have a two-course diversity requirement which will be implemented in the fall for all incoming undergraduate students. Also emerging from this work is the Provost’s Committee for Diversity—a standing committee of student leaders that advise and contribute to projects related to diversity and inclusion, with particular attention to the experiences of our students of color.

This work that is being undertaken by our students is built on a long tradition of engagement and leadership on issues of social justice—by generations of students and alumni. This past Fall, in a first Black Alumni Summit, led by Tammee Thompson and Eric Woods, and just two weeks ago we celebrated our annual Patrick Healy Dinner, made possible through the leadership of our African American Alumni Board; its chair, an extraordinary alumnus Tyree Jones, who’s here today, and the selfless and dedicated efforts of Mannone Butler, who’s also here today.

As a university, Georgetown acknowledges its constituents—its students, faculty, staff, alumni, and those who have ultimate fiduciary responsibility—our Board of Directors. We are also a Catholic and Jesuit institution and we adhere to that identity intrinsic to us from our founding. We have pursued, given these varied constituencies, organic growth, participating, and change, emphasizing alignment among our multiple parts.

This approach, which defines our work as a university community, should guide our efforts to take the steps I suggest are needed to respond to the demands of this moment, where we are squarely facing unresolved issues of structural injustice in our nation; our efforts need to contribute to this moment in a way that is authentic to the work of the Academy and will certainly require all of us to locate and to contribute the capabilities and capacities commensurate with the moral urgency we now face. This is work we will all do together.

Based on this belief in our shared responsibilities—and the conviction that though our university is by no means as wealthy as many of our peers, we have our values, we have our community approach: I suggest that we make four commitments as we move forward in the pursuit of ameliorating the structural injustices that pervade our racial divides. I provide this framework with an understanding that the work I recommend will require the engagement of our community.

Nothing I propose can occur without the appropriate participation of our faculties, our school executive committees, our consultative bodies, our formal governance structures.

Where Should the Journey Take Us? Four New Commitments

First, to celebrate this work, we, at Georgetown, need a “center of gravity”—a place where we can bring together colleagues—faculty, students, post-docs, public intellectuals and more—to ensure that we are contributing to the work of advancing the disciplines in the field of African-American Studies.

Georgetown will build upon the recent decision of the Executive Committee of the College to establish a major in African American Studies and will now seek to create a Department and/or a broader Interdisciplinary Program of African American Studies.

Departments provide homes for mentoring of faculty, for tenure, for majors and minors. They are our most common form of academic structure. But the essential elements are a charter of some permanence, faculty citizenship that is long lasting, a size that permits diversity of intellectual approaches, and a space that is home. Across our nation’s universities, a Department of African-American Studies has been the most common approach of organization.

At the same time, we recognize that to draw from the full resources of our community, it will be important to determine how best to capture the “inter-disciplinary” character of this work. How can a Department of African American Studies support this interdisciplinary character?

Given our location in Washington and the strengths of our existing schools, we need to ensure that any such unit will provide a home for the full range of disciplines that can contribute to building the field of African American Studies. Indeed, we need every discipline that can contribute insights to the building of this field.

Following our conversation today, I will work with Provost Groves in establishing a Working Group—a Working Group on Racial Injustice: A Georgetown Response—that will explore a range of questions, including, whether the structure of a traditional department will support inter-disciplinary work that crosses the full range of schools and disciplines that can contribute to this effort. Perhaps we need a department and an Interdisciplinary program. These are important issues for us to consider as we move forward.

A second step would amplify this “center of gravity.” We must establish a new Research Center that studies racial injustice and the persistent and enduring legacy of racism and segregation in America. We need to address the structural causes at the root of persistent inequalities—persistent racial injustice in American society.

This would not be the first such research center in the Academy, but again, an institution with our distinct set of characteristics must engage the continuing challenges that flow from the tragic history of slavery and segregation of our nation. Persistent differences in educational outcomes, health disparities, economic participation—the increasing inequalities across our nation—all require a sustained and enduring commitment that only the Academy can provide.

Understanding and solving these issues cannot be achieved with one body of knowledge, within one discipline. We need teams of researchers working to make progress, and we need to tap all the relevant external funding institutions to make the research center sustainable. In Georgetown’s way of life, faculty and students would be working side-by-side in these teams. At this moment, we should bring the resources of a new research center at Georgetown to bear on these matters.

This Research Center will provide a new framework for integrating the resources of Georgetown in the service of justice. By doing so we become congruent with Decree 4, which in 1974, in the Thirty-Second General Congregation of the Jesuits, set forth a “redefinition” of the Order. We have been living with this redefinition here, since 1974 and it reads: ‘The mission of the Society of Jesus today is the service of faith, of which the promotion of justice is an absolute requirement’.18

I will look to this Working Group, to be established shortly after this Town Hall, to identify how best to realize this vision. There will be many important issues that must be confronted: the scope of such a research center; its relationship to our schools and departments; how would a new research center connect and complement other centers that already are at work here at the University doing crucially important work—how will it relate to a new department, a new interdisciplinary commitment to African-American Studies?

Third, we can’t accomplish either of these two goals without a critical mass of new colleagues dedicated to this work. We will commit to recruit the number of faculty commensurate with the commitments needed to support a Department and/or Interdisciplinary Center, and a Research Center. As we expand the number of faculty recruited to support this work, we expect that some of these faculty can contribute to the educational program; some, the research program; some, to both.

In addition, we will be strengthened through additional graduate fellowships and post-doctoral opportunities.

As first steps, for the coming year, we will authorize four immediate recruitments of new members of the faculty and four recruitments for the following year. These will be new—new lines above and beyond what we would normally have been engaged in in our recruitment efforts over these next two years. And again, I will ask the Working Group to recommend areas of focus for faculty recruitment, working collaboratively with the deans, the department chairs, and our faculty colleagues.

Finally, to support these efforts, we will need a new senior officer who will support the efforts of establishing a department/interdisciplinary program, a research center, and especially supporting the recruitment of this cohort of faculty. Such an officer will bring a focus to faculty recruitment, working collaboratively with our Provost, our Vice-Provosts, with our Office of Institutional Diversity, Equity and Affirmative Action. We will work with our senior leadership from the Main campus, the Law Center, and the Medical Campus—Bill Treanor, Ed Healton, Bob Groves…all share in their vision that this is a moment where we can significantly strengthen our community.

Surely other elements besides these four will emerge—you may already have some ideas, just as I unfold mine! It is my intent that these four commitments provide the architecture for taking this next step for Georgetown and a Working Group will ensure we engage this moment in a manner consistent with our shared style of governance.

But let me be very clear on one point. I commit Georgetown to making these important new investments. These will happen. But we will do this as we do all important and successful work that we have all been a part of here—together, by listening to one another, letting all who can contribute to participate in the new endeavors, and working together to achieve our goals. These discussions will not be about whether we do these things, but how best to do them in the urgency of the moment.

We will find the very best in each other, and together, we will find new ways to bring out the very best of Georgetown.

Conclusion

So in closing: why is this a priority, now?

…because our social and political culture has not been remedied; and, in fact, from a set of recent events, it has deteriorated;

…because there is a holy impatience among the African-American community that delay is just another way of saying NO;

…because the moral imperative for complete social justice continues to summon us not to discussion but to action and that summons will not go away–we ignore social morality at our peril.

Why us? Why this educational response?

I offer these reflections from three perspectives:

I offer these reflections as an educator—we live our lives here as a University—there is work that we do in our society that is distinctive—we support the formation of young people—our students; the inquiry—the scholarship and research of our faculty; we contribute to the common good—and this commitment to our educational service to the common good demands that we use our rich resources and moral prestige to contribute to this same common good.

I offer these reflections as a citizen—with an obligation to seek and to implement actions for the common good of our country.

And I offer these reflections in my role—as the executive responsible for overseeing our mission, I must call us to honor our corporate commitment to the faith traditions not only of our Jesuit and Catholic tradition but to all the other faith communities who have a home in our community and call us to stand for justice.

I am a product of this place. I offer these reflections as the beneficiary of the friendships that I have shared here over four decades. I hope some of you will recognize your influence on me in these words. I am grateful. We now need to proceed as a community. You all represent the very best humane implementation of this act of justice.

I am presenting this charge that we do our part, as an important educational community, to hasten the common good and the shared justice for those for whom it has been too long denied.

I wish to thank you for your presence here today—and I’ll be happy to take any questions that you may have. And as you depart, we will share with you copies of the charge document that will guide our working group that will be established shortly after our conversation today. The charge to the working group will give you a sense of some of the specific areas of focus I would like us as a community to engage and it’s an invitation to all of you to be a part of this ongoing conversation.

So again thank you for being here and I’d be happy to take your questions on anything that we discussed.

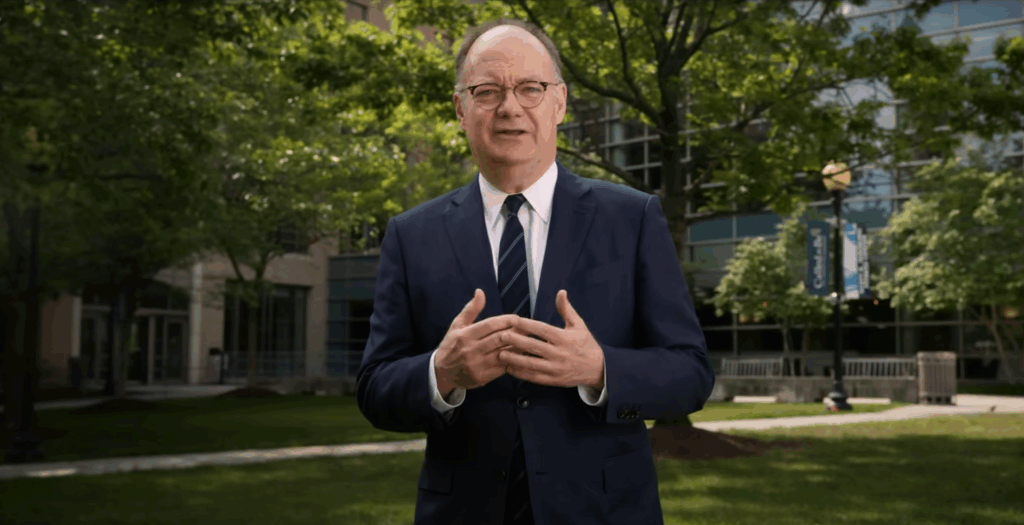

Georgetown President Makes Major Commitments to Address Racial Injustice

Citing the recent incidents and long history of racial injustice in the United States, Georgetown President John J. DeGioia laid out a series of commitments to inform the university’s work to address racial injustice, in a speech to the university community yesterday.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. “Acceptance Speech.” Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014.

- Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “On Whose Shoulders the Research Stands.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, 23 May 2014.

- Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “The Case for Reparations.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, June 2014.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Smiley, Tavis, and Tamika Thompson. “Fact Sheet: Outcomes for Young, Black Men.” Tavis Smiley Reports: Too Important to Fail. PBS, 13 Sept. 2011.

- Ibid.

- Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, October 2015.

- Hagler, Jamal. “8 Facts You Should Know About the Criminal Justice System and People of Color.” Center for American Progress. 28 May 2015.

- “Seven Themes of Catholic Social.” Sharing Catholic Social Teaching: Challenges and Directions. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Communications, 2015.

- Francis. “Visit to the Community of Varginha [Manguinhos], Rio De Janeiro, 25 July 2013.

- Arrupe, Pedro, and Kevin F. Burke. Pedro Arrupe: Essential Writings. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2004, Print.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. “Acceptance Speech.” Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB, 2014.

- Bromwich, David. Moral Imagination: Essays. Princeton University Press, 2014.

- Maalouf, Amin. In the Name of Identity: Violence and the Need to Belong. New York: Arcade, 2001. Print.

- Faust, Drew Gilpin. “John Hope Franklin: Race & the Meaning of America.” The New York Review of Books, 17 Dec. 2015.

- Ibid.

- Padberg, John W. Documents of the 31st and 32nd General Congregations of the Society of Jesus: An English Translation of the Official Latin Texts of the General Congregations and of the Accompanying Papal Documents. Saint Louis: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1977. Print.